Why the Low Fixed Charge regulations should be removed

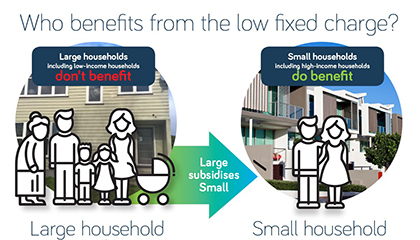

Some households are paying more for a connection to the electricity grid than other households. Households who use more power are, in effect, cross-subsidising households that use less power.

The Government's Electricity Price Review in 2019 recommended the low fixed charge regulations should be removed. The Government has accepted this recommendation in principle and has asked officials to report back on acceptable transition arrangements that manage the impacts on consumers.

What’s the problem?

Those paying higher charges include families and vulnerable consumers who live in uninsulated homes and can’t afford energy efficient appliances or technologies. This can:

- create a perverse incentive for income-constrained households to under-heat their homes to save money, which can have knock-on health and education issues, especially for children;

- increasingly favour wealthier consumers over the longer-term as they can afford the capital investment in solar, efficient lights, insulation and the like. This will increase the cost-shifting from wealthy consumers to less-wealthy consumers;

- will frustrate the uptake of the electric vehicles which is arguably the best opportunity to de-carbonise our economy;

- act as a subsidy for dual fuel customers (ie. gas). This is a perverse outcome given our renewable electricity generation profile in New Zealand; and

- increase the complexity of tariffs and double the number of tariffs on offer, increasing costs for retailers and ultimately consumers as well as making it more difficult to understand electricity pricing.

These problems are being caused by a regulation called Electricity (Low Fixed Charge Tariff Option for Domestic Consumers) Regulations 2004. Commonly known as the low fixed charge.

What do they do?

The regulations require retailers to offer domestic consumers low daily fixed charge tariff options of no more than 30c per day (excluding GST).

What are daily fixed charges, and what are they for?

Fixed daily charges are used by networks and retailers to recover those costs which do not vary with the amount of electricity consumed.

In total, the actual fixed costs can be well over $2.00 per day for typical residential users – the low fixed charge regulations mean that users who qualify can be charged no more than 30 cents per day to cover these fixed costs.

Fifteen cents goes to the lines company and 15 cents to the retailer.

The flip-side of the low fixed charge requirement is that networks and retailers have to significantly increase the variable charges (the price charged per unit of electricity) for consumers who choose a low-fixed tariff. Under-recovery of costs from low-fixed charge customers means they also need to increase prices for those customers who aren’t on low-fixed charges.

Who can access the low fixed charge?

Anyone can choose a low-fixed charge option. However, the regulations explicitly guarantee that residential consumers using less than 8,000kWh per year (or 9,000kWh per year for consumers in the lower South Island) will be better-off if they choose the low-fixed option compared to the standard rate.

What’s the problem?

Because of the low fixed charge regulations, some households are paying more for a connection to the electricity grid than other households.

Who is paying more than they should?

In general, above-average consumers of electricity are paying more than the actual cost of their connection to the grid. In contrast, homes which use less electricity are contributing less than the actual cost of their connection.

In effect, the regulations have created a cross-subsidy. Those paying the higher prices are subsidising those paying the lower prices.

But shouldn’t higher users pay more?

For electricity, yes. But they shouldn’t also have to stump up more for their lines charge. Lines costs are largely fixed, meaning they do not vary depending on how much electricity is flowing through lines. All things being equal, a customer in any single town or city should be paying the same amount for their lines connection as their neighbour, regardless of energy consumption (measured in kilowatt hours).

Is 30 cents a day a good deal?

Exceptional. The actual cost of a connection to the grid varies from place to place, but a typical actual amount is $2.50 a day for the lines component alone.

The 15 cents per day of the fixed charge that goes to the lines company contributes less than five percent to the cost of providing and maintaining the local lines network.

However, because the low-fixed charge introduces a cross-subsidy between customers, a ‘good deal’ for some customers becomes a ‘bad deal’ for other customers.

But surely only a minority of households use less than 8,000 kWh a year?

The average electricity consumption of a New Zealand household in the year ending June 2020 was 7,099 kWh. The Electricity Networks Association estimates about 60 percent of households are eligible for the low fixed charge, meaning the low fixed charge is available to the majority of households.

Again – what’s the problem?

Lines companies require income to pay for new lines, or upgrade and repair existing lines. There are 152,000 km of lines in the distribution network. The amount that lines companies can recover is regulated by the Commerce Commission. If people are paying less than their share, then other households need to pay more, which creates the cross-subsidy.

How did the regulations come about?

The regulations had two goals. The first was to encourage households to use less electricity, meaning decreased demand for new generation such as hydro schemes which require rivers to be dammed.

This was an understandable goal in 2004, when electricity demand was rising by three percent a year. But new technology such as more efficient appliances, and better insulation, has resulted in total demand for electricity staying the same for the past 10 years, despite there being more people and homes. This means householders are on average using less electricity than they were.

A second goal was to help households on low incomes by reducing the fixed component of their power bill.

Does it help people on lower incomes?

Yes and no. Some low-income households are low users. However, there are many low-income households that use more than 8,000 kWh a year. These include larger families living in homes with no other energy source (eg, gas, solar, wood-burners) and which are poorly insulated. These households are worse off, as these higher-use households are subsidising the electricity supply costs of smaller households who live in well-insulated modern homes with energy-efficient modern appliances.

In addition, there are a large number of wealthy households who qualify for the low-fixed charge subsidy. These are households who may have invested in alternative heating (gas or wood-burners), home insulation, and efficient lighting or other appliances. They may also live in modern houses or apartments which require much less energy to heat.

Over time, a growing proportion of people on higher incomes will benefit more from the regulations. This is because higher income people can afford technologies to reduce their usage (e.g. home insulation, LED lights, solar panels). This means more and more of the costs of the electricity system will be shifted onto consumers who cannot access or afford these energy-saving technologies.

Is this just a way for lines companies to make more money?

No. Lines companies are natural monopolies and as such the total revenues they can earn are curbed by the Commerce Commission. Lines companies cannot make more money from the regulations being removed.

Are there any other issues?

Yes. Lines companies and retailers want to adjust the way they price for their service to reflect new technologies. These changes are motivated by the desire to firstly lessen peaks in demand so as to reduce the need for costly infrastructure upgrades, and secondly, to better align charging with true costs across all consumers. The low fixed charge and its underlying regulations presents a legal barrier to introducing these new pricing options.

And because the flip-side of the low fixed charge is higher variable charges (the price per unit of electricity), these higher variable charges can effectively discourage people from using electricity.

Amongst other things, this can have undesirable consequences in terms of New Zealand’s CO2 emissions and healthy homes. Examples include:

- Slowing down the uptake of electric vehicles due to higher-than-necessary charging costs, prolonging the use of high CO2 emitting fuels such as petrol and diesel. (As a largely renewable energy source, electricity has a low carbon footprint.)

- Discouraging people on low-incomes from heating their homes adequately, with undesirable consequences for their health.

What should happen?

Both ENA and the Electricity Retailers' Association (ERANZ) were pleased that the Government has, in principle, accepted the recommendation of the 2019 Electrcity Price Review that the low fixed charge (LFC) regulations should be removed. It was agreed that they were causing outcomes which were directly contrary to the original intent.

Both ENA and ERANZ are working closely with government officials to design transition arrangements for the removal of the LFC regulations that manage the impacts of the change on consumers. We are encouraging the Government to implement the transition away from the LFC as soon as possible.

Is there a better way?

The low-fixed charge regulations fail to give targeted energy support to those who need it most and cause other undesirable distortions which give rise to environmental and economic costs.

Internationally, energy-related income supplements (such as the Government's winter energy subsidy), or percentage rebates on bills appear to be more successful at giving support to those suffering energy hardship, without causing significant other adverse outcomes.

Key design aspects which help deliver these positive outcomes include: using welfare metrics as the basis for qualifying for support (e.g. holding a community services card) and funding such measures via general taxation rather than increasing prices for other electricity customers.

The Labour-New Zealand First coalition government has taken the first steps to implementing one of these approaches — announcing a winter energy supplement for beneficiaries and superannuitants of $450 for singles and $700 for couples.

Compared to the low fixed charge, the energy supplement is a more targeted approach to helping those users pay their power bill. Now that low-income households are being supported, and with the need to encourage electric vehicles, the low fixed charges should be removed.